The secret to living a long, independent and healthy life may be a concept that’s highly debated and inconsistently studied. Frailty, by most accounts, is a measure of an individual’s robustness and resilience or their ability to recover from events like illness and injury.

It turns out that frailty is a remarkably powerful predictor of negative outcomes that most older adults, their families and health care providers want to avoid, including falls, emergency department visits, hospitalizations, nursing homes admissions and death.

Over one million Canadians are living with frailty and, with Canada’s rapidly ageing population, many more Canadians are likely to be living with it in the future. How well we are able to support these growing ranks of older adults will depend on our ability to identify and deliver effective interventions for those living with frailty.

Research evidence has shown that while some interventions can be beneficial to individuals with frailty, other treatments can actually cause harm and lead to worse outcomes.

First, let’s hear the good news. Exercise programs can improve a person’s overall function and reduce the presence of frailty in older adults, and possibly even reverse it. Interprofessional team-based care provided in community settings can also help support older adults living with frailty to stay more healthy and independent than might otherwise be possible. Other interventions, like chemotherapy, however, can actually result in negative outcomes such as falls, emergency department visits, hospitalizations, and death. As a consequence, frailty is and must be a key consideration in the provision of high-quality cancer care for older patients.

Clearly, knowing whether an older adult is living with frailty, and to what degree, is vital information for care providers and patients making health care decisions. How you determine who does and does not have frailty, though, is where researchers begin to part ways. Disagreement over how to measure frailty stems from differences in understanding what frailty is.

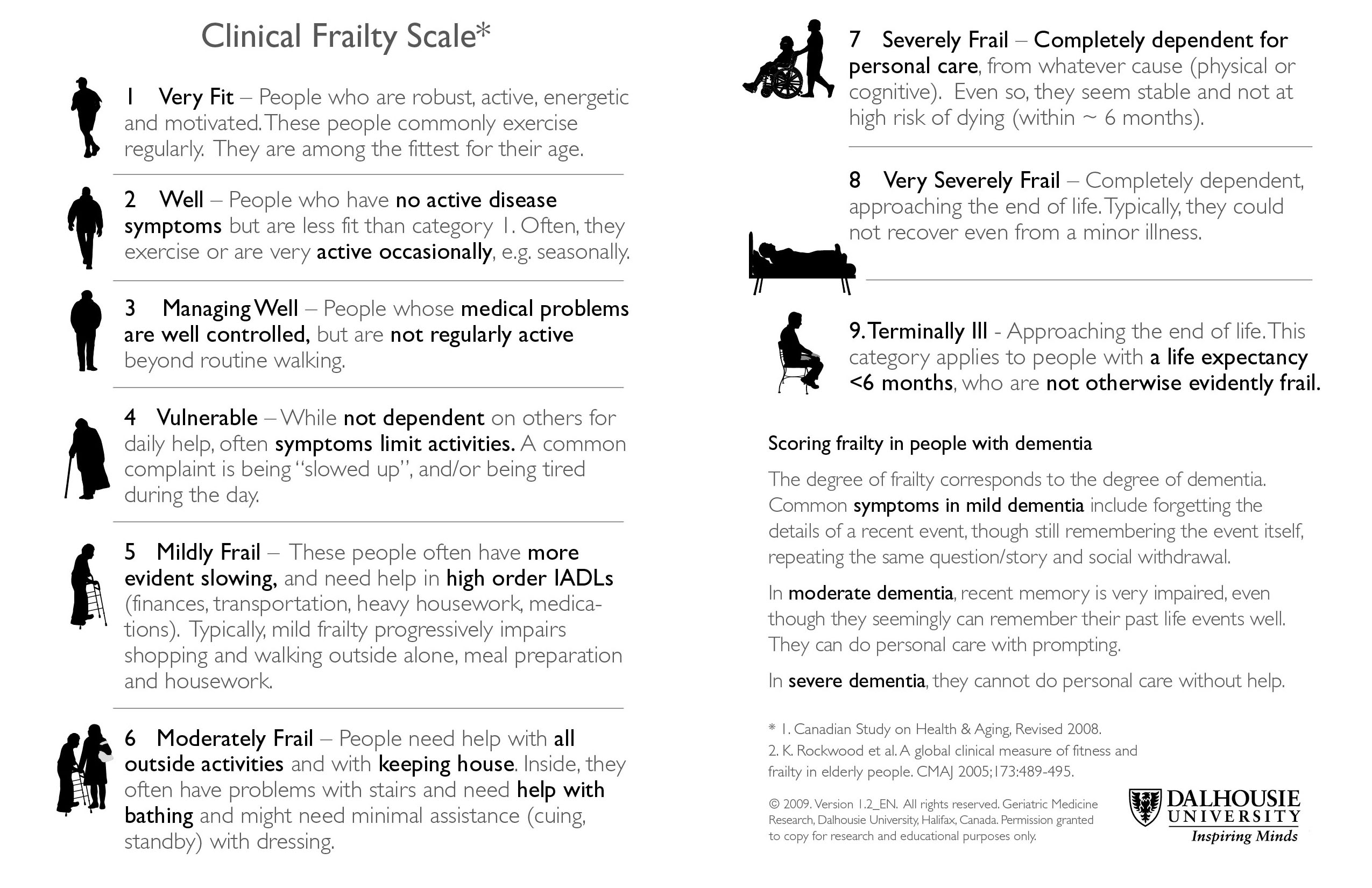

The Clinical Frailty Scale, developed by Canada’s own Dr. Kenneth Rockwood, posits that frailty is the outcome of an accumulation of deficits. A deficit is a health or functional challenge an individual has, such as an illness, symptom, injury, or mobility limitation. The scale uses a list of dozens of deficits to determine an individual’s level of frailty. The individual challenges that older adults have doesn’t matter as much, according to Rockwood, than the number of challenges they have. Furthermore, it matters more that you count a large number of deficits – 50 to 80 – than the same deficits in each patient. So, if you count 80 deficits in two older adults, and each has 30 deficits, they will both have frailty scores of 3.75/10, but may not have any deficits in common. Rockwood has also developed a scale to help identify what having 3.75 on the frailty scale means. Individuals with that score are managing well, but are at risk for having their conditions limit their activities.

Image courtesy of Dalhousie University.

On the other hand, Dr. Linda Fried and her colleagues at Columbia University advance the concept of a frailty phenotype. Frailty, Fried says, is a specific condition that results from slow walking speed, exhaustion, unintentional weight loss, weak grip strength, and low levels of physical activity. Other challenges that older adults face are not part of frailty, according to this view.

When it comes to applying these concepts in clinical settings, Rockwood’s scale has been seen as being most relevant to primary care providers and others because it does not require any equipment or complicated measurements. Indeed, there are validated assessment tools, like the interRAI suite of Assessment Systems, commonly used across Canada to assess the care needs of those receiving home care and nursing home care, which can produce reliable frailty scores based on the observations made during a routine assessment.

No matter how you assess frailty in older patients, what care providers and patients do with that measurement is incredibly important. Knowing that an individual is living with frailty will not tell you which treatment is best for them, but can tell you whether you need to proceed with caution or consider an alternate treatment course altogether. For instance, going back to our chemotherapy example, if a cancer patient is living with advanced frailty, chemotherapy may end up doing them more harm than good. If they are very old but not really frail – they likely should be offered the same therapy a younger person normally would. In other words, frailty measurement doesn’t give you a roadmap, but it does give you a starting point to determine what matters most to a patient and thus what sort of intervention may make the most sense for them.

There is intense disagreement in the research community about what frailty is and how to measure it, and building consensus on a definition and measurement criteria is important to achieving comparable research data. In primary and acute care settings, however, measuring frailty is not a part of standard care, but it should be considered when older adults interact with the health care system. Assessing an older patient for frailty has been likened by some as the difference between night-walking with a flashlight or in the dark; it doesn’t illuminate everything, but you can see if there’s something in front of you that you should avoid.

Date modified: 2019-07-31