Every year on January 31st, Canadians across the country engage in conversations online and in their communities about how mental health affects their neighbours, colleagues, loved ones and themselves. As many of us have come to understand, breaking the stigma around mental wellness through open conversation is an important first step toward making mental health supports and treatment easily accessible to Canadians who could benefit from them.

However, even with all these conversations about mental health, depression among older adults remains a misdiagnosed, undertreated and underreported mental health issue. While it’s estimated that between 5 – 10% of older Canadians living in the community will experience a depressive disorder that will require treatment, the number quadruples to 30 – 40% for older adults living in institutionalized settings.

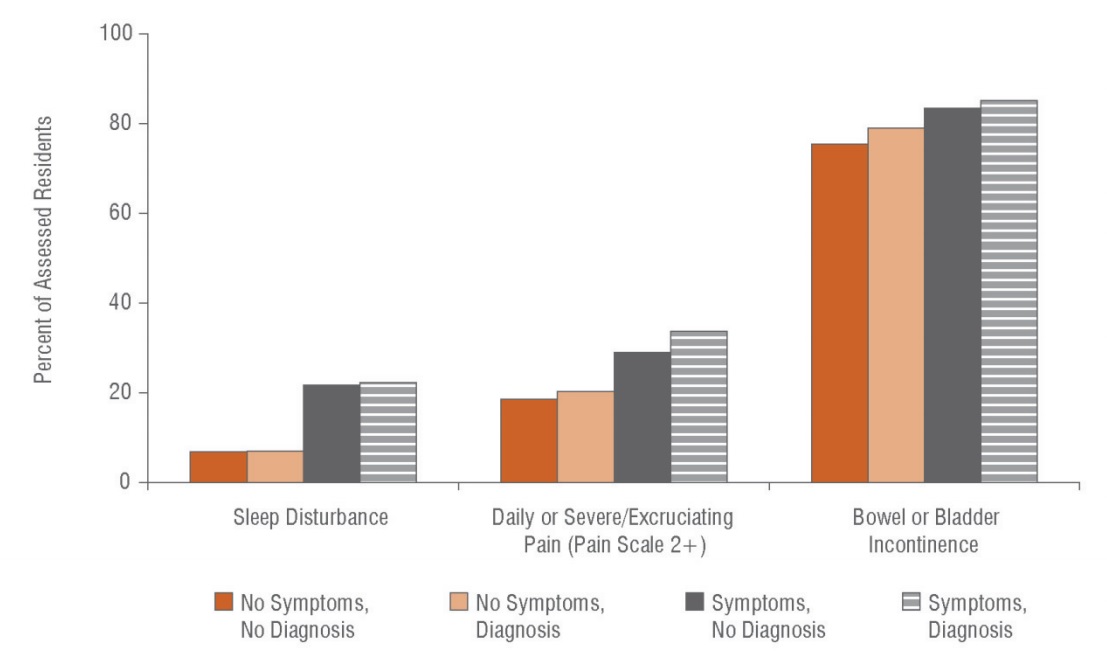

The increased prevalence of depressive symptoms among older adults living in long-term and residential care homes, either with or without a diagnosis of depression, may be due to the overall health of the population of the institutions. Older patients in long-term care homes tend to have more severe conditions and less function, which both contribute to a greater risk of a diagnosis of depression. A Canadian Institute for Health Information report found that residents of long-term care, nursing and personal care homes with symptoms of depression experienced significant medical, social, functional and quality-of-life challenges. However, the report further found that few residents received an evaluation from a mental health specialist or psychological therapy.

The differences in the rates of late life depression between older adults living in communities and those in institutions reflect differences in health status, but they also reveal a deep connection between the outer world we live in and the inner lives we experience.

Source: Canadian Institute for Health Information, Depression Among Seniors in Residential Care (2010)

The environments that older adults live in can be a supportive structure allowing them to thrive in their communities or can act as barriers that affect their social connections. The places where older adults live out their daily lives have a significant contribution to their mental health as well. The most important and frequently used built environment for older adults is their home. In retirement, and with family members being more mobile than ever before, older Canadians spend more time in their homes. In addition, physical decline, the loss of the ability to drive, lack of access to transportation options, and shrinking social networks all contribute to the amount of time older adults spend at home, which can all lead to depressive symptoms. The type of house can further contribute to depression. For example, it is understood that dwellings with fewer than two rooms contribute to depressive symptoms.

While the prevalence of depression is generally consistent across our older population, where you live plays a role in late life depression, and various environments affect social connections and mental health differently. Older adults in rural areas, for example, who live alone, perceive their income as inadequate and experience a functional decline, are at increased risk of depression. While older adults living in towns and urban centres that are undergoing higher levels of redevelopment experience a higher risk of developing depressive symptoms. This is because physical changes to the buildings in a community changes the social landscape of the neighbourhood as well.

Clearly, supporting older adults to live independently, with physical function and social connections, in a home they are content in is an important step to positively impacting their overall mental health. Our community outreach team – fittingly called Independence at Home – aims to do just that.

Our Community Outreach Team was launched in February 2016 with funding support from the MOHLTC via the Toronto Central Local Health Integration Network (TC-LHIN) as a partnership between Sinai Health System, the TC-LHIN, the University Health Network and others. Our interprofessional Community Outreach Team consists of a geriatrician, nurse, social worker, pharmacist, and a home care coordinator. This geriatrician-led interprofessional team accepts referrals from primary, home and community care providers, hospitals and emergency departments to better support older adults who may be struggling to stay independent in the community and would benefit from an interprofessional assessment. The team also supports older patients by connecting them with the right mix of home and community support, as well as in-home, clinic or inpatient rehabilitation care services that will help them regain or maintain their independence in the community.

First, let’s talk about late life depression, but then let’s take steps to address it at home, in the community and in residential care centres.

Date modified: 2018-01-29